EU

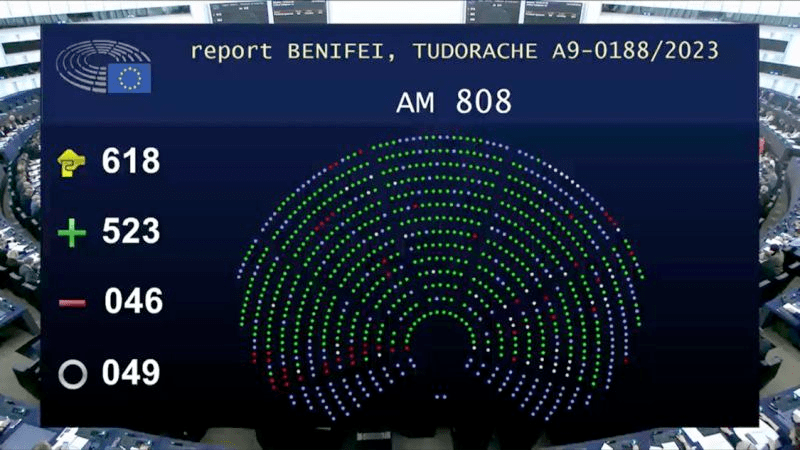

EU AI Act has been passed by EU parliament

It feels like we’ve been hearing about and talking about the EU AI Act for a very long time now. But on Wednesday 13th March 2024, the EU Parliament finally voted to approve the Act. While this is a major milestone, we haven’t crossed the finish line. There are a few steps to complete, although these are minor steps and are part of the process.

The remaining timeline is:

- The EU AI Act will undergo final linguistic approval by lawyer-linguists in April. This is considered a formality step.

- It will then be published in the Official EU Journal

- 21 days after being published it will come into effect (probably in May)

- The Prohibited Systems provisions will come into force six months later (probably by end of 2024)

- All other provisions in the Act will come into force over the next 2-3 years

If you haven’t already started looking at and evaluating the various elements of AI deployed in your organisation, now is the time to start. It’s time to prepare and explore what changes, if any, you need to make. If you don’t the penalties for non-compliance are hefty, with fines of up to €35 million or 7% of global turnover.

The first thing you need to address is the Prohibited AI Systems and the EU AI Act outlines the following and will need to be addressed before the end of 2024:

- Manipulative and Deceptive Practices: systems that use subliminal techniques to materially distort a person’s decision-making capacity, leading to significant harm. This includes systems that manipulate behaviour or decisions in a way that the individual would not have otherwise made.

- Exploitation of Vulnerabilities: systems that target individuals or groups based on age, disability, or socio-economic status to distort behaviour in harmful ways.

- Biometric Categorisation: systems that categorise individuals based on biometric data to infer sensitive information like race, political opinions, or sexual orientation. This prohibition does not cover any labelling or filtering of lawfully acquired biometric datasets, such as images. There are also exceptions for law enforcement.

- Social Scoring: systems designed to evaluate individuals or groups over time based on their social behaviour or predicted personal characteristics, leading to detrimental treatment.

- Real-time Biometric Identification: The use of real-time remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement is heavily restricted, with allowances only under narrowly defined circumstances that require judicial or independent administrative approval.

- Risk Assessment in Criminal Offences: systems that assess the risk of individuals committing criminal offences based solely on profiling, except when supporting human assessment already based on factual evidence.

- Facial Recognition Databases: systems that create or expand facial recognition databases through untargeted scraping of images are prohibited.

- Emotion Inference in Workplaces and Educational Institutions: The use of AI to infer emotions in sensitive environments like workplaces and schools is banned, barring exceptions for medical or safety reasons.

In addition to the timeline given above we also have:

- 12 months after entry into force: Obligations on providers of general purpose AI models go into effect. Appointment of member state competent authorities. Annual Commission review of and possible amendments to the list of prohibited AI.

- after 18 months: Commission implementing act on post-market monitoring

- after 24 months: Obligations on high-risk AI systems specifically listed in Annex III, which includes AI systems in biometrics, critical infrastructure, education, employment, access to essential public services, law enforcement, immigration and administration of justice. Member states to have implemented rules on penalties, including administrative fines. Member state authorities to have established at least one operational AI regulatory sandbox. Commission review and possible amendment of the last of high-risk AI systems.

- after 36 months: Obligations for high-rish AI systems that are not prescribed in Annex III but are intended to be used as a safety component of a product, or the AI is itself a product, and the product is required to undergo a third-party conformity assessment under existing specific laws, for example, toys, radio equipment, in vitro diagnostic medical devices, civil aviation security and agricultural vehicles.

The EU has provided an official compliance check that helps identify which parts of the EU AI Act apply in a given use case.

EU Digital Services Act

The Digital Services Act (DSA) applies to a wide variety of online services, ranging from websites to social networks and online platforms, with a view to “creating a safer digital space in which the fundamental rights of all users of digital services are protected”.

In November 2020, the European Union introduced a new legislation called the Digital Services Act (DSA) to regulate the activities of tech companies operating within the EU. The aim of the DSA is to create a safer and more transparent online environment for EU citizens by imposing new rules and responsibilities on digital service providers. This includes online platforms such as social media, search engines, e-commerce sites, and cloud services. The provisions in the DSA Act will apply from 17th February 2024, thus giving affected parties time to ensure compliance.

The DSA aims to address a number of issues related to digital services, including:

- Ensuring that digital service providers take responsibility for the content on their platforms and that they have effective measures in place to combat illegal content, such as hate speech, terrorist content, and counterfeit goods.

- Requiring digital service providers to be more transparent about their advertising practices, and to disclose more information about the algorithms they use to recommend content.

- Introducing new rules for online marketplaces to prevent the sale of unsafe products and to ensure that consumers are protected when buying online.

- Strengthening the powers of national authorities to enforce these rules and to hold digital service providers accountable for any violations.

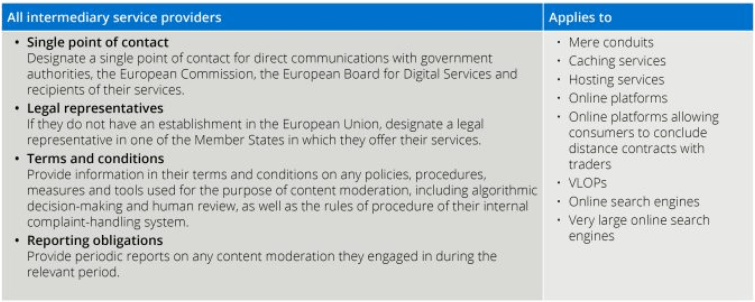

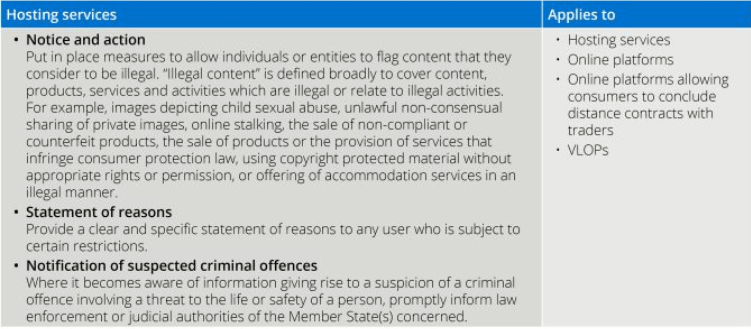

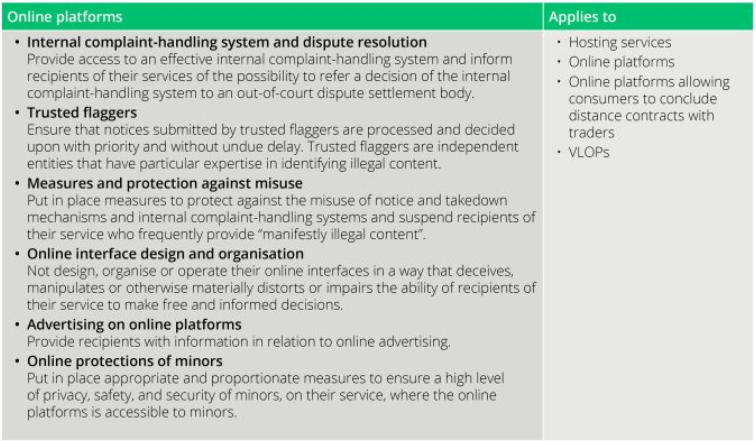

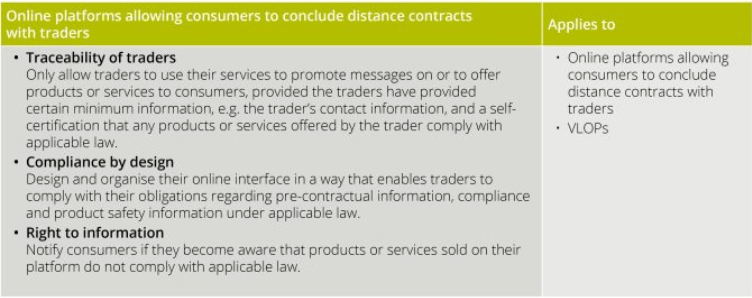

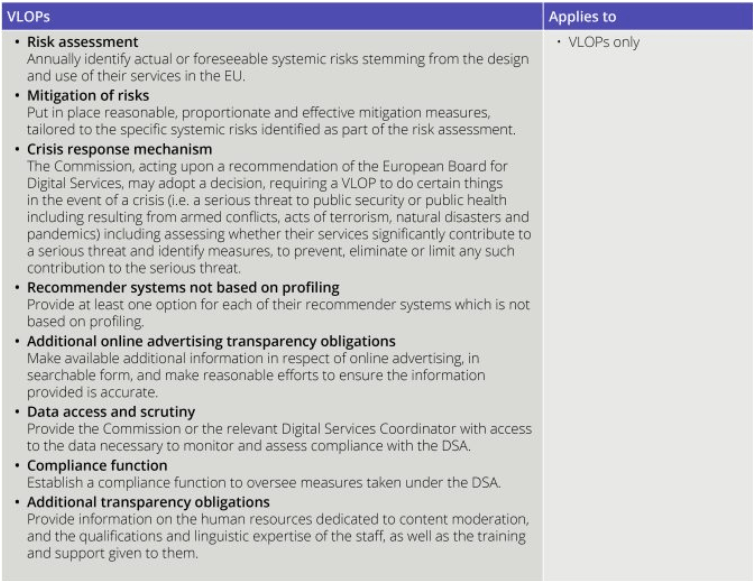

The DSA takes a layered approach to regulation. The basic obligations under the DSA apply to all online intermediary service providers, additional obligations apply to providers in other categories, with the heaviest regulation applying to very large online platforms (VLOPs) and very large online service engines (VLOSEs).

The four categories are:

- Intermediary service providers are online services which consist of either a “mere conduit” service, a “caching” service; or a “hosting” service. Examples include online search engines, wireless local area networks, cloud infrastructure services, or content delivery networks.

- Hosting services are intermediary service providers who store information at the request of the service user. Examples include cloud services and services enabling sharing information and content online, including file storage and sharing.

- Online Platforms are hosting services which also disseminate the information they store to the public at the user’s request. Examples include social media platforms, message boards, app stores, online forums, metaverse platforms, online marketplaces and travel and accommodation platforms.

- (a) VLOPs are online platforms having more than 45 million active monthly users in the EU (representing 10% of the population of the EU). (b) VLOSEs are online search engines having more than 45 million active monthly users in the EU (representing 10% of the population of the EU).

Arther Cox provide a useful table of obligations for each of these categories.

You must be logged in to post a comment.