Vector Database

Vector Databases – Part 8 – Creating Vector Indexes

Building upon the previous posts, this post will explore how to create Vector Indexes and the different types. In the next post I’ll demonstrate how to explore wine reviews using the Vector Embeddings and the Vector Indexes.

Before we start working with Vector Indexes, we need to allocate some memory within the Database where these Vector Indexes can will located. To do this we need to log into the container database and change the parameter for this. I’m using a 23.5ai VM. On the VM I run the following:

sqlplus system/oracle@freeThis will connect you to the contain DB. No run the following to change the memory allocation. Be careful not to set this too high, particularly on the VM. Probably the maximum value would be 512M, but in my case I’ve set it to a small value.

alter system set vector_memory_size = 200M scope=spfile;You need to bounce the database. You can do this using SQL commands. If you’re not sure how to do that, just restart the VM.

After the restart, log into your schema and run the following to see if the parameter has been set correctly.

show parameter vector_memory_size;

NAME TYPE VALUE

------------------ ----------- -----

vector_memory_size big integer 208M

We can see from the returned results we have the 200M allocated (ok we have 208M allocated). If you get zero displayed, then something went wrong. Typically, this is because you didn’t run the command at the container database level.

You only need to set this once for the database.

There are two types of Vector Indexes:

- Inverted File Flat Vector Index (IVF). The inverted File Flat (IVF) index is the only type of Neighbor Partition vector index supported. Inverted File Flat Index (IVF Flat or simply IVF) is a partitioned-based index which balances high search quality with reasonable speed. This index is typically disk based.

- In-Memory Neighbor Graph Vector Index. Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) is the only type of In-Memory Neighbor Graph vector index supported. HNSW graphs are very efficient indexes for vector approximate similarity search. HNSW graphs are structured using principles from small world networks along with layered hierarchical organization. As the name suggests these are located in-memory. See the step above for allocating Vector Memory space for these indexes.

Let’s have a look at creating each of these.

CREATE VECTOR INDEX wine_desc_ivf_idx

ON wine_reviews_130k (embedding)

ORGANIZATION NEIGHBOR PARTITIONS

DISTANCE COSINE

WITH TARGET ACCURACY 90 PARAMETERS (type IVF, neighbor partitions 10);As with your typical create index, you define the column and table. The column must have the data type of VECTOR. We can then say what the distance measure should be, the target accuracy and any additional parameters required. Although the parameters part is not required, and the defaults will be used instead.

For other in-memory index we have

CREATE VECTOR INDEX wine_desc_idx ON wine_reviews_130k (embedding)

ORGANIZATION inmemory neighbor graph

distance cosine

WITH target accuracy 95;You can do some testing or evaluating to determine the accuracy of the Vector Index. You’ll need a test string which has been converted into a Vector by the same embedding mode used on the original data. See my previous posts for some example of how to do this.

declare

q_v VECTOR;

report varchar2(128);

begin

q_v := to_vector(:query_vector);

report := dbms_vector.index_accuracy_query(

OWNER_NAME => 'VECTORAI',

INDEX_NAME => 'WINE_DESC_HNSW_IDX',

qv => q_v, top_K =>10,

target_accuracy =>90 );

dbms_output.put_line(report);

end; This entry was posted in 23ai, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged Vector Database, Vector Embeddings, Vector Indexes.

Vector Databases – Part 7 – Some simple SQL Queries

It can be very straightforward to use Vectors using SQL. It’s just a simple SQL query, with some additional Vector related requirements. The examples given below are a collection of some simple examples. These aren’t my examples, but they come from either documentation or from other examples people have come up with. I’ve tried to include references back to the original sources for these, and if I’ve missed any or referred to the wrong people, just let me know and I’ll correct the links.

In my next post on Vector Databases, I’ll explore a slightly more complex data set. I’ll use the Wine dataset used in a previous post and Vector Search to see if I can find a suitable wine. Some years ago, I had posts and presentations on machine learning to recommend wine. Using Vector Search should give us better recommendations (hopefully)!

This first example is from the Oracle Documentation on Vector Search. This contains very simple vectors for the embedding. In my previous posts I’ve shown how to generate more complex vectors from OpenAI and Cohere.

-- In the VECTORAI user run the following

-- create demo table -- Galazies

CREATE TABLE if not exists galaxies (

id NUMBER,

name VARCHAR2(50),

doc VARCHAR2(500),

embedding VECTOR);

-- Insert some data

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (1, 'M31', 'Messier 31 is a barred spiral galaxy in the Andromeda constellation which has a lot of barred spiral galaxies.', '[0,2,2,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (2, 'M33', 'Messier 33 is a spiral galaxy in the Triangulum constellation.', '[0,0,1,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (3, 'M58', 'Messier 58 is an intermediate barred spiral galaxy in the Virgo constellation.', '[1,1,1,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (4, 'M63', 'Messier 63 is a spiral galaxy in the Canes Venatici constellation.', '[0,0,1,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (5, 'M77', 'Messier 77 is a barred spiral galaxy in the Cetus constellation.', '[0,1,1,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (6, 'M91', 'Messier 91 is a barred spiral galaxy in the Coma Berenices constellation.', '[0,1,1,0,0]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (7, 'M49', 'Messier 49 is a giant elliptical galaxy in the Virgo constellation.', '[0,0,0,1,1]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (8, 'M60', 'Messier 60 is an elliptical galaxy in the Virgo constellation.', '[0,0,0,0,1]');

INSERT INTO galaxies VALUES (9, 'NGC1073', 'NGC 1073 is a barred spiral galaxy in Cetus constellation.', '[0,1,1,0,0]');

COMMIT;

-- How similar is galazy M31 to all the others

-- using VECTOR_DISTANCE to compare vectors.

-- the smaller the distance measure indicates simularity

-- Default distance measure = COSINE

SELECT g1.name AS galaxy_1,

g2.name AS galaxy_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(g2.embedding, g1.embedding) AS distance

FROM galaxies g1,

galaxies g2

WHERE g1.id = 1 and g2.id <> 1

ORDER BY distance ASC;

-- Euclidean Distance

SELECT g1.name AS galaxy_1,

g2.name AS galaxy_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(g2.embedding, g1.embedding, EUCLIDEAN) AS distance

FROM galaxies g1, galaxies g2

WHERE g1.id = 1 and g2.id <> 1

ORDER BY distance ASC;

-- DOT Product

SELECT g1.name AS galaxy_1,

g2.name AS galaxy_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(g2.embedding, g1.embedding, DOT) AS distance

FROM galaxies g1, galaxies g2

WHERE g1.id = 1 and g2.id <> 1

ORDER BY distance ASC;

-- Manhattan

SELECT g1.name AS galaxy_1,

g2.name AS galaxy_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(g2.embedding, g1.embedding, MANHATTAN) AS distance

FROM galaxies g1, galaxies g2

WHERE g1.id = 1 and g2.id <> 1

ORDER BY distance ASC;

-- Hamming

SELECT g1.name AS galaxy_1,

g2.name AS galaxy_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(g2.embedding, g1.embedding, HAMMING) AS distance

FROM galaxies g1, galaxies g2

WHERE g1.id = 1 and g2.id <> 1

ORDER BY distance ASC;Again from the Oracle documentation, here is an example with a more complex vector.

------------------------------------------

-- Here is a more complex Vector example

-- From Oracle Documentation

------------------------------------------

DROP TABLE if not exists doc_queries PURGE;

CREATE TABLE doc_queries (id NUMBER, query VARCHAR2(500), embedding VECTOR);

DECLARE

e CLOB;

BEGIN

e:=

'[-7.73346797E-002,1.09683955E-002,4.68435362E-002,2.57333983E-002,6.95586428E-00'||

'2,-2.43412293E-002,-7.25011379E-002,6.66433945E-002,3.78751606E-002,-2.22354475E'||

'-002,3.02388351E-002,9.36625451E-002,-1.65204913E-003,3.50606232E-003,-5.4773859'||

'7E-002,-7.5879097E-002,-2.72218436E-002,7.01764375E-002,-1.32512336E-003,3.14728'||

'022E-002,-1.39147148E-001,-7.52705336E-002,2.62449421E-002,1.91645715E-002,4.055'||

'73137E-002,5.83701171E-002,-3.26474942E-002,2.0509012E-002,-3.81141738E-003,-7.1'||

'8656182E-002,-1.95893757E-002,-2.56917924E-002,-6.57705888E-002,-4.39117625E-002'||

',-6.82357177E-002,1.26592368E-001,-3.46683599E-002,1.07687116E-001,-3.96954492E-'||

'002,-9.06721968E-003,-2.4109887E-002,-1.29214963E-002,-4.82468568E-002,-3.872307'||

'76E-002,5.13443872E-002,-1.40985977E-002,-1.87066793E-002,-1.11725368E-002,9.367'||

'76772E-002,-6.39425665E-002,3.13162468E-002,8.61801133E-002,-5.5481784E-002,4.13'||

'125418E-002,2.0447813E-002,5.03717586E-002,-1.73418857E-002,3.94522659E-002,-7.2'||

'6833269E-002,3.13266069E-002,1.2377765E-002,7.64856935E-002,-3.77447419E-002,-6.'||

'41075056E-003,1.1455299E-001,1.75497644E-002,4.64923214E-003,1.89623125E-002,9.1'||

'3506597E-002,-8.22509527E-002,-1.28537193E-002,1.495138E-002,-3.22528258E-002,-4'||

'.71280375E-003,-3.15563753E-003,2.20409594E-002,7.77796134E-002,-1.927099E-002,-'||

'1.24283969E-001,4.69769612E-002,1.78121701E-002,1.67152807E-002,-3.83916795E-002'||

',-1.51029453E-002,2.10864041E-002,6.86845928E-002,-7.4719809E-002,1.17681816E-00'||

'3,3.93113159E-002,6.04066066E-002,8.55340436E-002,3.68878953E-002,2.41579115E-00'||

'2,-5.92489541E-002,-1.21883564E-002,-1.77226216E-002,-1.96259264E-002,8.51236377'||

'E-003,1.43039867E-001,2.62829307E-002,2.96348184E-002,1.92485824E-002,7.66567141'||

'E-002,-1.18600562E-001,3.01779062E-002,-5.88010997E-002,7.07774982E-002,-6.60426'||

'617E-002,6.44619241E-002,1.29240509E-002,-2.51785964E-002,2.20869959E-004,-2.514'||

'38171E-002,5.52265197E-002,8.65883753E-002,-1.83726232E-002,-8.13263431E-002,1.1'||

'6624301E-002,1.63392909E-002,-3.54643688E-002,2.05128491E-002,4.67337575E-003,1.'||

'20488718E-001,-4.89500947E-002,-3.80397178E-002,6.06209273E-003,-1.37961926E-002'||

',4.68355882E-031,3.35873142E-002,6.20040558E-002,2.13472452E-002,-1.87379227E-00'||

'3,-5.83158981E-004,-4.04266678E-002,2.40761992E-002,-1.93725452E-002,9.3763724E-'||

'002,-3.02913114E-002,7.67844869E-003,6.11112304E-002,6.02455214E-002,-6.38855845'||

'E-002,-8.03523697E-003,2.08786246E-003,-7.45898336E-002,8.74964818E-002,-5.02371'||

'937E-002,-4.99385223E-003,3.37120108E-002,8.99377018E-002,1.09540671E-001,5.8501'||

'102E-002,1.71627291E-002,-3.26152593E-002,8.36912021E-002,5.05600758E-002,-9.737'||

'63615E-002,-1.40264994E-002,-2.07926836E-002,-4.20163684E-002,-5.97197041E-002,1'||

'.32461395E-002,2.26361351E-003,8.1473738E-002,-4.29272018E-002,-3.86809185E-002,'||

'-8.24682564E-002,-3.89646105E-002,1.9992901E-002,2.07321253E-002,-1.74706057E-00'||

'2,4.50415723E-003,4.43851873E-002,-9.86309871E-002,-7.68082142E-002,-4.53814305E'||

'-003,-8.90906602E-002,-4.54972908E-002,-5.71065396E-002,2.10020249E-003,1.224947'||

'07E-002,-6.70659095E-002,-6.52298108E-002,3.92126441E-002,4.33384106E-002,4.3899'||

'6181E-002,5.78813367E-002,2.95345876E-002,4.68395352E-002,9.15119275E-002,-9.629'||

'58392E-003,-5.96637605E-003,1.58674959E-002,-6.74034096E-003,-6.00510836E-002,2.'||

'67188111E-003,-1.10706768E-003,-6.34015873E-002,-4.80389707E-002,6.84534572E-003'||

',-1.1547043E-002,-3.44865513E-003,1.18979132E-002,-4.31232266E-002,-5.9022788E-0'||

'02,4.87607308E-002,3.95954074E-003,-7.95252472E-002,-1.82770658E-002,1.18264249E'||

'-002,-3.79164703E-002,3.87993976E-002,1.09805465E-002,2.29136664E-002,-7.2278082'||

'4E-002,-5.31538352E-002,6.38669729E-002,-2.47980515E-003,-9.6999377E-002,-3.7566'||

'7699E-002,4.06541862E-002,-1.69874367E-003,5.58868013E-002,-1.80723771E-033,-6.6'||

'5985467E-003,-4.45010923E-002,1.77929532E-002,-4.8369132E-002,-1.49722975E-002,-'||

'3.97582203E-002,-7.05247298E-002,3.89178023E-002,-8.26886389E-003,-3.91006246E-0'||

'02,-7.02963024E-002,-3.91333885E-002,1.76661201E-002,-5.09723537E-002,2.37749107'||

'E-002,-1.83419678E-002,-1.2693027E-002,-1.14232123E-001,-6.68751821E-002,7.52167'||

'869E-003,-9.94713791E-003,6.03599809E-002,6.61353692E-002,3.70595567E-002,-2.019'||

'52495E-002,-2.40410417E-002,-3.36526595E-002,6.20064288E-002,5.50279953E-002,-2.'||

'68641673E-002,4.35859226E-002,-4.57317568E-002,2.76936609E-002,7.88119733E-002,-'||

'4.78852056E-002,1.08523415E-002,-6.43479973E-002,2.0192951E-002,-2.09538229E-002'||

',-2.2202393E-002,-1.0728148E-003,-3.09607089E-002,-1.67067181E-002,-6.03572279E-'||

'002,-1.58187654E-002,3.45828459E-002,-3.45360823E-002,-4.4002533E-003,1.77463517'||

'E-002,6.68234832E-004,6.14458732E-002,-5.07084019E-002,-1.21073434E-002,4.195981'||

'85E-002,3.69152687E-002,1.09461844E-002,1.83413982E-001,-3.89185362E-002,-5.1846'||

'0497E-002,-8.71620141E-003,-1.17692262E-001,4.04785499E-002,1.07505821E-001,1.41'||

'624091E-002,-2.57720836E-002,2.6652012E-002,-4.50568087E-002,-3.34110335E-002,-1'||

'.11387551E-001,-1.29796984E-003,-6.51671961E-002,5.36890551E-002,1.0702607E-001,'||

'-2.34011523E-002,3.97406481E-002,-1.01149324E-002,-9.95831117E-002,-4.40197848E-'||

'002,6.88989647E-003,4.85475454E-003,-3.94048765E-002,-3.6099229E-002,-5.4075513E'||

'-002,8.58292207E-002,1.0697281E-002,-4.70785573E-002,-2.96272673E-002,-9.4919120'||

'9E-003,1.57316476E-002,-5.4926388E-002,6.49022609E-002,2.55531631E-002,-1.839057'||

'17E-002,4.06873561E-002,4.74951901E-002,-1.22502812E-033,-4.6441108E-002,3.74079'||

'868E-002,9.14599106E-004,6.09740615E-002,-7.67391697E-002,-6.32521287E-002,-2.17'||

'353106E-002,2.45231949E-003,1.50869079E-002,-4.96984981E-002,-3.40828523E-002,8.'||

'09691194E-003,3.31339166E-002,5.41345142E-002,-1.16213948E-001,-2.49572527E-002,'||

'5.00682592E-002,5.90037219E-002,-2.89178211E-002,8.01460445E-003,-3.41945067E-00'||

'2,-8.60121697E-002,-6.20261126E-004,2.26721354E-002,1.28968194E-001,2.87655368E-'||

'002,-2.20255274E-002,2.7228903E-002,-1.12029864E-002,-3.20301466E-002,4.98079099'||

'E-002,2.89051589E-002,2.413591E-002,3.64605561E-002,6.26017479E-003,6.54632896E-'||

'002,1.11282602E-001,-3.60428065E-004,1.95987038E-002,6.16615731E-003,5.93593046E'||

'-002,1.50377362E-003,2.95319762E-002,2.56325547E-002,-1.72190219E-002,-6.5816819'||

'7E-002,-4.08149995E-002,2.7983617E-002,-6.80195764E-002,-3.52494679E-002,-2.9840'||

'0577E-002,-3.04043181E-002,-1.9352382E-002,5.49411364E-002,8.74160081E-002,5.614'||

'25127E-002,-5.60747795E-002,-3.43311466E-002,9.83581021E-002,2.01142877E-002,1.3'||

'193069E-002,-3.22583504E-002,8.54402035E-002,-2.20514946E-002]';

INSERT INTO doc_queries VALUES (13, 'different methods of backup and recovery', e);

COMMIT;

END;

/The next example is a really nice one, so check out the link to the original post. They give some charts which plot the vectors. You can use these to easily visualize the data points and why we get our answers to the queries.

-----------------------

-- Another example

-- taken from https://medium.com/@ludan.aguirre/oracle-23ai-vector-search-its-all-about-semantics-f9224ac6d4bb

-----------------------

CREATE TABLE if not exists PARKING_LOT (

VEHICLE VARCHAR2(10),

LOCATION VECTOR

);

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR1','[7,4]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR2','[3,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR3','[6,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK1','[10,7]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK2','[4,7]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK3','[2,3]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK4','[5,6]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE1','[4,1]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE2','[6,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE3','[2,6]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE4','[5,8]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV1','[8,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV2','[9,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV3','[1,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV4','[5,4]');

select

v1.vehicle as vehicle_1,

v2.vehicle as vehicle_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(v1.location,v2.location,EUCLIDEAN) as distance

from parking_lot v1, parking_lot v2

where v1.vehicle='CAR1'

order by distance asc

FETCH FIRST 6 ROWS ONLY;

select

v1.vehicle as vehicle_1,

v2.vehicle as vehicle_2,

VECTOR_DISTANCE(v1.location,v2.location,EUCLIDEAN) as distance

from parking_lot v1, parking_lot v2

where v1.vehicle='TRUCK4'

order by distance asc

FETCH FIRST 6 ROWS ONLY;I’ll have another post on using Vector Search to explore and make Wine recommendations based on personalized tastes etc.

This entry was posted in 23ai, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged Vector Database, Vector Embedding, Vector Search.

Vector Databases – Part 6 – SQL function/trigger using OpenAI

In my previous post, I gave examples of using Cohere to create vector embeddings using SQL and of using a Trigger to populate a Vector column. This post extends those concepts, and in this post, we will use OpenAI.

Warning: At the time of writing this post there is a bug in Oracle 23.5 and 23.6 that limits the OpenAI key to a maximum of 130 characters. The newer project-based API keys can generate keys which are greater than 130 characters. You might get lucky with getting a key of appropriate length or you might have to generate several. An alternative to to create a Legacy (or User Key). But there is no guarantee how long these will be available.

Assuming you have an OpenAI API key of 130 characters or less you can follow the remaining steps. This is now a know bug for the Oracle Database (23.5, 23.6) and it should be fixed in the not-too-distant future. Hopefully!

In my previous post I’ve already added to the ACL (Access Control List) the ability to run against any host. The command to do that was easy, perhaps too easy, as it will allow the ‘vectorai’ schema to access any website etc. I really should have limited it to the address of Cohere and in this post to OpenAI. Additionally, I should have limited to specific port numbers. That’s a bit of security risk and in your development, test and production environment you should have these restrictions.

In the ‘vectorai’ schema we need to create a new credential to store the OpenAI key. I’ve called this credential CRED_OPENAI

DECLARE

jo json_object_t;

BEGIN

jo := json_object_t();

jo.put('access_token', '...');

dbms_vector.create_credential(

credential_name => 'CRED_OPENAI',

params => json(jo.to_string));

END;Next, we can test calling the embedding model from OpenAI. The embedding model used in this example is called ‘text-embedding-3-small’

declare

input clob;

params clob;

output clob;

v VECTOR;

begin

-- input := 'hello';

input := 'Aromas include tropical fruit, broom, brimstone and dried herb. The palate isnt overly expressive, offering unripened apple, citrus and dried sage alongside brisk acidity.';

params := '

{

"provider": "OpenAI",

"credential_name": "CRED_OPEAI",

"url": "https://api.openai.com/v1/embeddings",

"model": "text-embedding-3-small"

}';

v := dbms_vector.utl_to_embedding(input, json(params));

output := to_clob(v);

dbms_output.put_line('VECTOR');

dbms_output.put_line('--------------------');

dbms_output.put_line(dbms_lob.substr(output,1000)||'...');

exception

when OTHERS THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (SQLERRM);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (SQLCODE);

end;And in a similar manner to the Cohere example we can create a trigger to popular a Vector column.

Warning: You should not mix the use of different embedding models when creating vectors. A vector column should only have vectors created by the same embedding models, and not from two different models.

create or replace trigger vec_test_trig2

before insert or update on vec_test

for each row

declare

params clob;

v vector;

begin

params := '{

"provider": "OpenAI",

"credential_name": "CRED_OPEAI",

"url": "https://api.openai.com/v1/embeddings",

"model": "text-embedding-3-small"

}';

v := dbms_vector.utl_to_embedding(:new.col2, json(params));

:new.col3 := v;

end;This entry was posted in 23ai, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged Vector Database, Vector Embedding.

Vector Databases – Part 5 – SQL function to call External Embedding model

There are several ways to create Vector embedding. In previous posts, I’ve provided some examples (see links below). These examples were externally created and then loaded into the database.

But what if we want to do this internally in the database? We can use SQL and create a new vector embedding every time we insert or update a record.

The following examples are based on using the Oracle 23.5ai Virtual Machine. These examples illustrate using a Cohere Embedding model. At time of writing this post using OpenAI generates an error. In theory it should work and might work with subsequent database releases. All you need to do is include your OpenAI key and model to use.

Step-1 : DBA tasks

Log into the SYSTEM schema for the 23.5ai Database on the VM. You can do this using SQLcl, VS Code, SQL Developer or whatever is your preferred tool. I’m assuming you have a schema in the DB you want to use. In my example, this schema is called VECTORAI. Run the following:

BEGIN

DBMS_NETWORK_ACL_ADMIN.APPEND_HOST_ACE(

host => '*',

ace => xs$ace_type(privilege_list => xs$name_list('connect'),

principal_name => 'vectorai',

principal_type => xs_acl.ptype_db));

END;

grant create credential to vectorai;This code will open the database to the outside world to all available site, host => ‘*’. This is perhaps a little dangerous and should be restricted to only the site you want access to. Then grant an additional privilege to VECTORAI which allows it to create credentials. We’ll use this in the next step.

Steps 2 – In Developer Schema (vectorai)

Next, log into your developer schema. In this example, I’m using a schema called VECTORAI.

Step 3 – Create a Credential

Create a credential which points to your API Key. In this example, I’m connecting to my Cohere API key.

DECLARE

jo json_object_t;

BEGIN

jo := json_object_t();

jo.put('access_token', '...');

dbms_vector.create_credential(

credential_name => 'CRED_COHERE',

params => json(jo.to_string));

END;Enter your access token in the above, replacing the ‘…’

Step 4 – Test calling the API to return a Vector

Use the following code to test calling an Embedding Model passing some text to parse.

declare

input clob;

params clob;

output clob;

v VECTOR;

begin

-- input := 'hello';

input := 'Aromas include tropical fruit, broom, brimstone and dried herb. The palate isnt overly expressive, offering unripened apple, citrus and dried sage alongside brisk acidity.';

params := '

{

"provider": "cohere",

"credential_name": "CRED_COHERE",

"url": "https://api.cohere.ai/v1/embed",

"model": "embed-english-v2.0"

}';

v := dbms_vector.utl_to_embedding(input, json(params));

output := to_clob(v);

dbms_output.put_line('VECTOR');

dbms_output.put_line('--------------------');

dbms_output.put_line(dbms_lob.substr(output,1000)||'...');

exception

when OTHERS THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (SQLERRM);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (SQLCODE);

end;This should generate something like the following with the Vector values.

VECTOR

--------------------

[-1.33886719E+000,-3.61816406E-001,7.50488281E-001,5.11230469E-001,-3.63037109E-001,1.5222168E-001,1.50390625E+000,-1.81674957E-004,-4.65087891E-002,-7.48535156E-001,-8.62426758E-002,-1.24414062E+000,-1.02148438E+000,1.19433594E+000,1.41503906E+000,-7.02148438E-001,-1.66015625E+000,2.39990234E-001,8.68652344E-001,1.90917969E-001,-3.17871094E-001,-7.08007812E-001,-1.29882812E+000,-5.63476562E-001,-5.65429688E-001,-7.60498047E-002,-1.40820312E+000,1.01367188E+000,-6.45996094E-001,-1.38574219E+000,2.31054688E+000,-1.21191406E+000,6.65893555E-002,1.02148438E+000,-8.16040039E-002,-5.17578125E-001,1.61035156E+000,1.23242188E+000,1.76879883E-001,-5.71777344E-001,1.45214844E+000,1.30957031E+000,5.30395508E-002,-1.38476562E+000,1.00976562E+000,1.36425781E+000,8.8671875E-001,1.578125E+000,7.93457031E-001,1.03027344E+000,1.33007812E+000,1.08300781E+000,-4.21875E-001,-1.23535156E-001,1.31933594E+000,-1.21191406E+000,4.49462891E-001,-1.06640625E+000,5.26367188E-001,-1.95214844E+000,1.58105469E+000,...The Vector displayed above has been truncated, as the vector contains 4096 dimensions. If you’d prefer to work with a smaller number of dimensions you could use the ’embed-english-light-v2.0′ embedding model.

An alternative way to test this is using SQLcl and run the following:

var params clob;

exec :params := '{"provider": "cohere", "credential_name": "CRED_COHERE", "url": "https://api.cohere.ai/v1/embed", "model": "embed-english-v2.0"}';

select dbms_vector.utl_to_embedding('hello', json(:params)) from dual;In this example, the text to be converted into a vector is ‘hello’

Step 5 – Create an Insert/Update Trigger on table.

Let’s create a test table.

create table vec_test (col1 number, col2 varchar(200), col3 vector);Using the code from the previous step, we can create an insert/update trigger.

create or replace trigger vec_test_trig

before insert or update on vec_test

for each row

declare

params clob;

v vector;

begin

params := '

{

"provider": "cohere",

"credential_name": "CRED_COHERE",

"url": "https://api.cohere.ai/v1/embed",

"model": "embed-english-v2.0"

}';

v := dbms_vector.utl_to_embedding(:new.col2, json(params));

:new.col3 := v;

end;We can easily test this trigger and the inserting/updating of the vector embedding using the following.

insert into vec_test values (1, 'Aromas include tropical fruit, broom, brimstone and dried herb', null);

select * from vec_test;

update VEC_TEST

set col2 = 'Wonderful aromas, lots of fruit, dark cherry and oak'

where col1 = 1;

select * from vec_test;When you inspect the table after the insert statement, you’ll see the vector has been added. Then after the update statement, you’ll be able to see we have a new vector for the record.

This entry was posted in 23ai, PL/SQL, SQL, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged 23ai, SQL, Vector Database, Vector Embedding, Vector Search.

Vector Databases – Part 3 – Vector Search

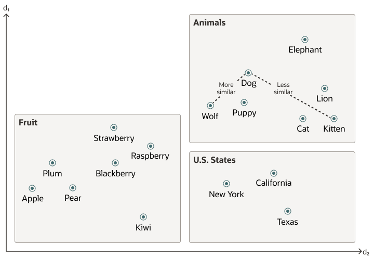

Searching semantic similarity in a data set is now equivalent to searching for nearest neighbors in a vector space instead of using traditional keyword searches using query predicates. The distance between “dog” and “wolf” in this vector space is shorter than the distance between “dog” and “kitten”. A “dog” is more similar to a “wolf” than it is to a “kitten”.

Vector data tends to be unevenly distributed and clustered into groups that are semantically related. Doing a similarity search based on a given query vector is equivalent to retrieving the K-nearest vectors to your query vector in your vector space.

Typically, you want to find an ordered list of vectors by ranking them, where the first row in the list is the closest or most similar vector to the query vector, the second row in the list is the second closest vector to the query vector, and so on. When doing a similarity search, the relative order of distances is what really matters rather than the actual distance.

Semantic search where the initial vector is the word “Puppy” and you want to identify the four closest words. Similarity searches tend to get data from one or more clusters depending on the value of the query vector, distance and the fetch size. Approximate searches using vector indexes can limit the searches to specific clusters, whereas exact searches visit vectors across all clusters.

Measuring distances in a vector space is the core of identifying the most relevant results for a given query vector. That process is very different from the well-known keyword filtering in the relational database world, which is very quick, simple and very very efficient. Vector distance functions involve more complicated computations.

There are several ways you can calculate distances to determine how similar, or dissimilar, two vectors are. Each distance metric is computed using different mathematical formulas. The time taken to calculate the distance between two vectors depends on many factors, including the distance metric used as well as the format of the vectors themselves, such as the number of vector dimensions and the vector dimension formats.

Generally, it’s best to match the distance metric you use to the one that was used to train the vector embedding model that generated the vectors. Common Distance metric functions include:

- Euclidean Distance

- Euclidean Distance Squared

- Cosine Similarity [most commonly used]

- Dot Product Similarity

- Manhattan Distance Hamming Similarity

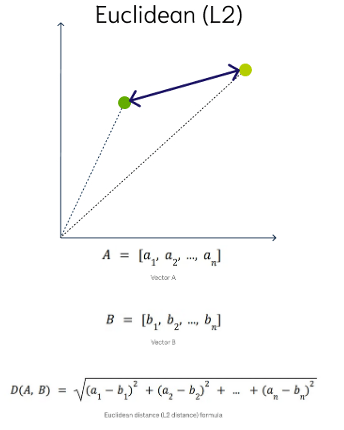

Euclidean Distance

This is a measure of the straight line distance between two points in the vector space. It ranges from 0 to infinity, where 0 represents identical vectors, and larger values represent increasingly dissimilar vectors. This is calculated using the Pythagorean theorem applied to the vector’s coordinates.

This metric is sensitive to both the vector’s size and it’s direction.

Euclidean Distance Squared

This is very similar to Euclidean Distance. When ordering is more important than the distance values themselves, the Squared Euclidean distance is very useful as it is faster to calculate than the Euclidean distance (avoiding the square-root calculation)

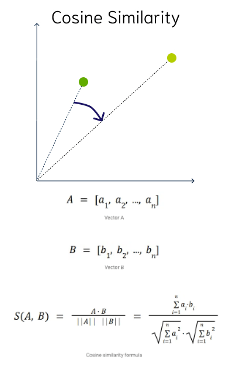

Cosine Similarity

This is the most commonly used distance measure. The cosine of the angle between two vectors – the larger the cosine, the closer the vectors. The smaller the angle, the bigger is its cosine. Cosine similarity measures the similarity in the direction or angle of the vectors, ignoring differences in their size (also called magnitude). The smaller the angle, the more similar are the two vectors. It ranges from -1 to 1, where 1 represents identical vectors, 0 represents orthogonal vectors, and -1 represents vectors that are diametrically opposed

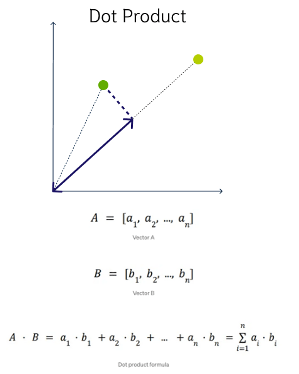

DOT Product Similarity

DOT product similarity of two vectors can be viewed as multiplying the size of each vector by the cosine of their angle. The larger the dot product, the closer the vectors. You project one vector on the other and multiply the resulting vector sizes. Larger DOT product values imply that the vectors are more similar, while smaller values imply that they are less similar. It ranges from -∞ to ∞, where a positive value represents vectors that point in the same direction, 0 represents orthogonal vectors, and a negative value represents vectors that point in opposite directions

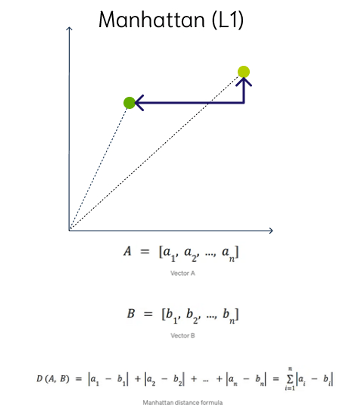

Manhattan Distance

This is calculated by summing the distance between the dimensions of the two vectors that you want to compare.

Imagine yourself in the streets of Manhattan trying to go from point A to point B. A straight line is not possible.

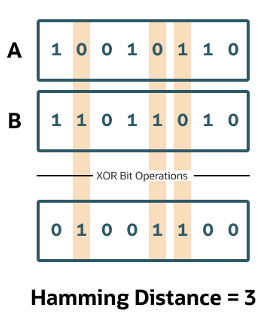

Hamming Similarity

This is the distance between two vectors represented by the number of dimensions where they differ. When using binary vectors, the Hamming distance between two vectors is the number of bits you must change to change one vector into the other. To compute the Hamming distance between two vectors, you need to compare the position of each bit in the sequence.

Check out my other posts in this series on Vector Databases.

This entry was posted in Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged Vector Database, Vector Embeddings, Vector Search.

Vector Databases – Part 2

In this post on Vector Databases, I’ll look at the main components:

- Vector Embedding Models. What they do and what they create.

- Vectors. What they represent, and why they have different sizes.

- Vector Search. An overview of what a Vector Search will do. A more detailed version of this is in a separate post.

- Vector Search Process. It’s a multi-step process and some care is needed.

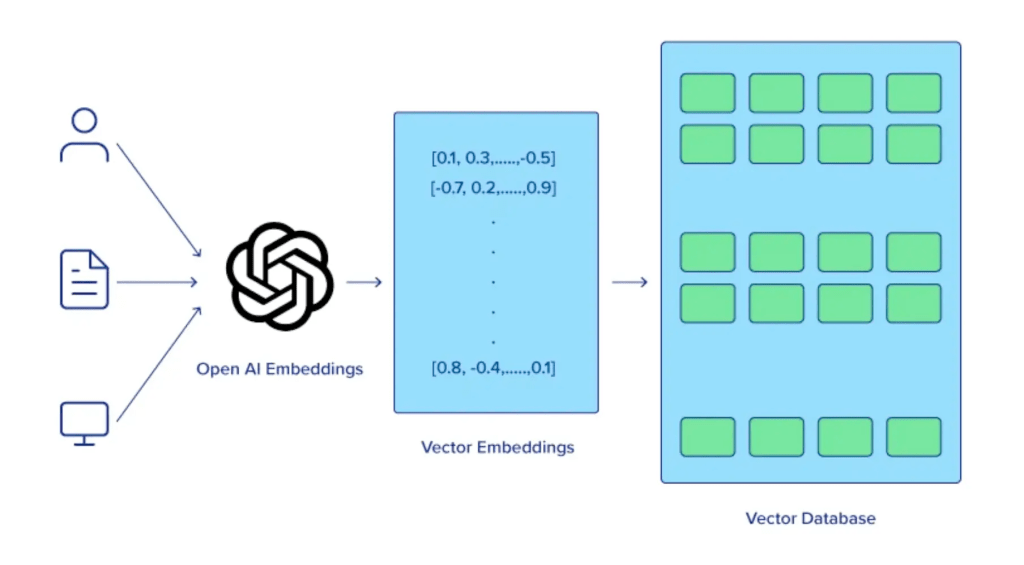

Vector Embedding Models

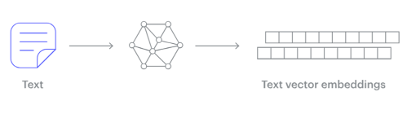

A vector embedding model is a type of machine learning model that transforms data into vectors (embeddings) in a high-dimensional space. These embeddings capture the semantic or contextual relationships between the data points, making them useful for tasks such as similarity search, clustering, and classification.

Embedding models are trained to convert the input data point (text, video, image, etc) into a vector (a series of numeric values). The model aims to identify semantic similarity with the input and map these to N-dimensional space. For example, the words “car” and “vehicle” have very different spelling but are semantically similar. The embedding model should map this to have similar vectors. Similarly with documents. The embedding model will map the documents to be able to group similar documents together (in N-dimensional space).

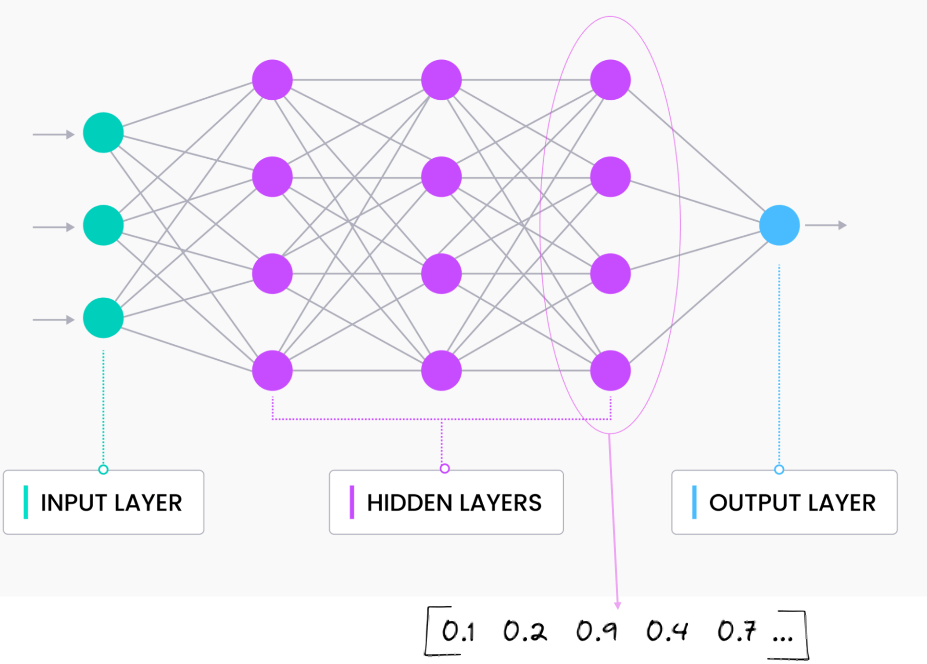

An embedding model is typically a Neural Network (NN) model. There are many different embedding models available from various vendor such as OpenAI, Cohere, etc., or you can build your own. Some models are open source and some are available for a fee. Typically, the output from the embedding model (the Vector) come from the last layer of the neural network

Vectors

A Vector is a sequence of numbers, called dimensions, used to capture the important “features” or “characteristics” of a piece of data. A vector is a mathematical object that has both magnitude (length) and direction. In the context of mathematics and physics, a vector is typically represented as an arrow pointing from one point to another in space, or as a list of numbers (coordinates) that define its position in a particular space.

Different Embedding Models create different numbers of Dimensions. Size is important with vectors as the greater the number number of dimensions the larger the Vector. The larger the number of dimensions the better the semantic similarity matches will be. As Vector size increases, so does space required to store them (not really a problem for Databases, but at Big Data scale it can be a challenge)

As vector size increases so does the Index space, and correspondingly search time can increase as the number of calculations for Distance Measure increases. There are various Vector indexes available to help with this (see my post covering this topic)

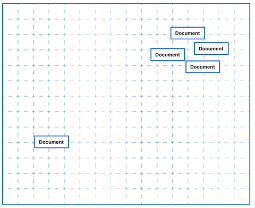

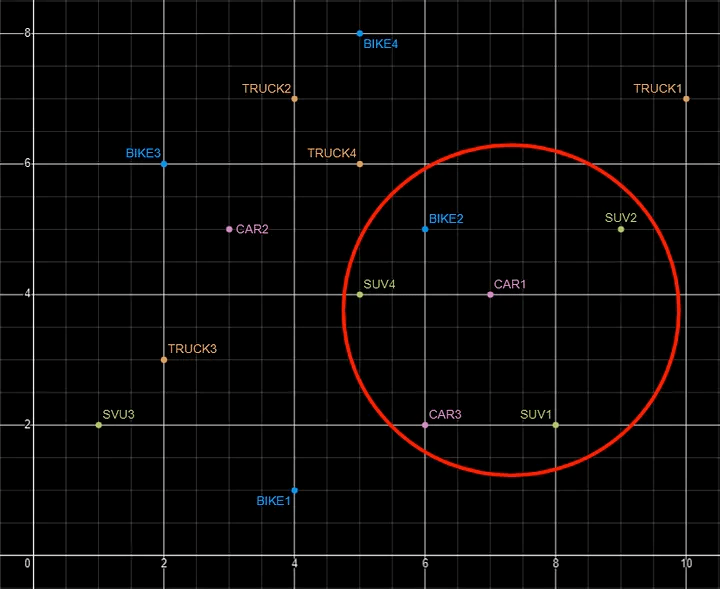

Basically, a vector is an array of numbers, where each number represents a dimension. It is easy for us to comprehend and visualise 2 dimensions. Here is an example of using 2 dimensions to represent different types of vehicles. The vectors give us a way to map or chart the data.

Here is SQL code for this data. I’ll come back to this data in the section on Vector Search.

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR1','[7,4]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR2','[3,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('CAR3','[6,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK1','[10,7]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK2','[4,7]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK3','[2,3]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('TRUCK4','[5,6]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE1','[4,1]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE2','[6,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE3','[2,6]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('BIKE4','[5,8]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV1','[8,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV2','[9,5]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV3','[1,2]');

INSERT INTO PARKING_LOT VALUES('SUV4','[5,4]');The vectors created by the embedding models can have a different number of dimensions. Common Dimension Sizes are:

- 100-Dimensional: Often used in older or simpler models like some configurations of Word2Vec and GloVe. Suitable for tasks where computational efficiency is a priority and the context isn’t highly complex.

- 300-Dimensional: A common choice for many word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe). Strikes a balance between capturing sufficient detail and computational feasibility.

- 512-Dimensional: Used in some transformer models and sentence embeddings. Offers a richer representation than 300-dimensional embeddings.

- 768-Dimensional: Standard for BERT base models and many other transformer-based models. Provides detailed and contextual embeddings suitable for complex tasks.

- 1024-Dimensional: Used in larger transformer models (e.g., GPT-2 large). Provides even more detail but requires more computational resources.

Many of the newer embedding models have >3000 dimensions!

- Cohere’s embedding model embed-english-v3.0 has 1024 dimensions.

- OpenAI’s embedding model text-embedding-3-large has 3072 dimensions.

- Hugging Face’s embedding model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 has 384 dimensions

Here is a blog post listing some of the embedding models supported by Oracle Vector Search.

Vector Search

Vector search is a method of retrieving data by comparing high-dimensional vector representations (embeddings) of items rather than using traditional keyword or exact-match queries. This technique is commonly used in applications that involve similarity search, where the goal is to find items that are most similar to a given query based on their vector representations.

For example, using the vehicle data given above, we can easily visualise the search for similar vehicles. If we took “CAR1” as our initiating data point and wanted to know what other vehicles are similar to it. Vector Search looks at the distance between “CAR1” and all other vehicles in the 2-dimensional space.

Vector Search becomes a bit more of a challenge when we have 1000+ dimensions, requiring advanced distance algorithms. I’ll have more on these in the next post.

Vector Search Process

The Vector Search process is divided into two parts.

The first part involved creating Vectors for your existing data and for any new data generated and needs to be stored. This data can be used for Semantic Similarity searches (part two of the process). The first part of the process takes your data, applies a vector embedding model to it, generates the vectors and stores them in your Database. When the vectors are stored, Vector Indexes can be created.

The second part if the process involves Vector Search. This involves having some data you want to search on (e.g. “CARS1” in the previous example). This data will need to be passed to the Vector Embedding model. A Vector for this data is generated. The Vector Search will use this vector to compare to all other vectors in the Database. The results returned will be those vectors (and their corresponding data) that closely match the vector being searched.

Check out my other posts in this series on Vector Databases.

This entry was posted in Oracle, Oracle Database, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged 23ai, Vector Database.

Vector Databases – Part 1

A Vector Database is a specialized database designed to efficiently store, search, and retrieve high-dimensional vectors, which are often used to represent complex data like images, text, or audio. Vector Databases handle the growing need for managing unstructured and semi-structured data generated by AI models, particularly in applications such as recommendation systems, similarity search, and natural language processing. By enabling fast and scalable operations on vector embeddings, vector databases play a crucial role in unlocking the power of modern AI and machine learning applications.

While traditional Databases are very efficient with storing, processing and searching structured data, but over the past 10+ years they have expanded to include many of the typical NoSQL Database features. This allows ‘modern’ multi-model Databases to be capable of processing structured, semi-structured and unstructured data all within a single Database. Such NoSQL capabilities now available in ‘modern’ multi-model Databases include unstructured data, dynamic models, columnar data, in-memory data, distributed data, big data volumes, high performance, graph data processing, spatial data, documents, streaming, machine learning, artificial intelligence, etc. That is a long list of features and I haven’t listed everything. As new data processing paradigms emerge, they are evaluated and businesses identify the usefulness or not of each. If the new data processing paradigms are determined to be useful, apart from some niche use cases, these capabilities are integrated by the vendors of these ‘modern’ multi-model Database vendors. We have seen similar happen with Vector Databases over the past year or so. Yes Vector Databases have existed for many years but we now have the likes of Oracle, PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server and even DB2 including Vector Embedding and Search.

Vector databases are specifically designed to store and search high-dimensional vector embeddings, which are generated by machine learning models. Here are some key use cases for vector databases:

1. Similarity Search:

- Image Search: Vector databases can be used to perform image similarity searches. For example, e-commerce platforms can allow users to search for products by uploading an image, and the system finds visually similar items using image embeddings.

- Document Search: In NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks, vector databases help find semantically similar documents or text snippets by comparing their embeddings.

2. Recommendation Systems:

- Product Recommendations: Vector databases enable personalized product recommendations by comparing user and item embeddings to suggest items that are similar to a user’s past interactions or preferences.

- Content Recommendation: For media platforms (e.g., video streaming or news), vector databases power recommendation engines by finding content that matches the user’s interests based on embeddings of past behavior and content characteristics.

3. Natural Language Processing (NLP):

- Semantic Search: Vector databases are used in semantic search engines that understand the meaning behind a query, rather than just matching keywords. This is useful for applications like customer support or knowledge bases, where users may phrase questions in various ways.

- Question-Answering Systems: Vector databases can be employed to match user queries with relevant answers by comparing their vector representations, improving the accuracy and relevance of responses.

4. Anomaly Detection:

- Fraud Detection: In financial services, vector databases help detect anomalies or potential fraud by comparing transaction embeddings with a normal behavior profile.

- Security: Vector databases can be used to identify unusual patterns in network traffic or user behavior by comparing embeddings of normal activity to detect security threats.

5. Audio and Video Processing:

- Audio Search: Vector databases allow users to search for similar audio files or songs by comparing audio embeddings, which capture the characteristics of sound.

- Video Recommendation and Search: Embeddings of video content can be stored and queried in a vector database, enabling more accurate content discovery and recommendation in streaming platforms.

6. Geospatial Applications:

- Location-Based Services: Vector databases can store embeddings of geographical locations, enabling applications like nearest-neighbor search for finding the closest points of interest or users in a given area.

- Spatial Queries: Vector databases can be used in applications where spatial relationships matter, such as in logistics and supply chain management, where efficient searching of locations is crucial.

7. Biometric Identification:

- Face Recognition: Vector databases store face embeddings, allowing systems to compare and identify faces for authentication or security purposes.

- Fingerprint and Iris Matching: Similar to face recognition, vector databases can store and search biometric data like fingerprints or iris scans by comparing vector representations.

8. Drug Discovery and Genomics:

- Molecular Similarity Search: In the pharmaceutical industry, vector databases can help in searching for chemical compounds that are structurally similar to known drugs, aiding in drug discovery processes.

- Genomic Data Analysis: Vector databases can store and search genomic sequences, enabling fast comparison and clustering for research and personalized medicine.

9. Customer Support and Chatbots:

- Intelligent Response Systems: Vector databases can be used to store and retrieve relevant answers from a knowledge base by comparing user queries with stored embeddings, enabling more intelligent and context-aware responses in chatbots.

10. Social Media and Networking:

- User Matching: Social networking platforms can use vector databases to match users with similar interests, friends, or content, enhancing the user experience through better connections and content discovery.

- Content Moderation: Vector databases help in identifying and filtering out inappropriate content by comparing content embeddings with known examples of undesirable content.

These use cases highlight the versatility of vector databases in handling various applications that rely on similarity search, pattern recognition, and large-scale data processing in AI and machine learning environments.

This post is the first in a series on Vector Databases. Some will be background details and some will be technical examples using Oracle Database. I’ll post links to the following posts below as they are published.

This entry was posted in Oracle, Oracle Database, Vector Database, Vector Embeddings and tagged 23ai, Oracle, Vector Database.

You must be logged in to post a comment.