23ai

SQL Firewall – Part 1

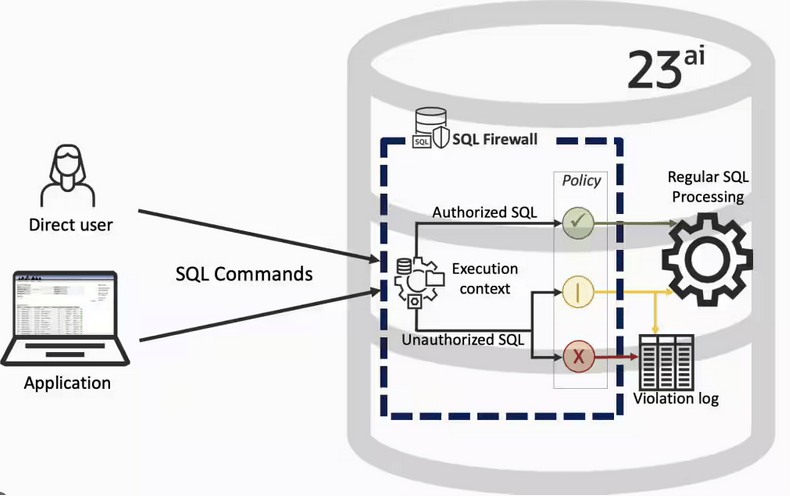

Typically, most IT architectures involve a firewall to act as a barrier, to monitor and to control network traffic. Its aim is to prevent unauthorised access and malicious activity. The firewall enforces rules to allow or block specific traffic (and commands/code). The firewall tries to protect our infrastructure and data. Over time, we have seen examples of how such firewalls have failed. We’ve also seen how our data (and databases) can be attacked internally. There are many ways to access the data and database without using the application. Many different people can have access to the data/database for many different purposes. There has been a growing need to push the idea of and the work of the firewall back to being closer to the data, that is, into the database.

SQL Firewall allows you to implement a firewall within the database to control what commands are allowed to be run on the data. With SQL Firewall you can:

- Monitor the SQL (and PL/SQL) activity to learn what the normal or typical SQL commands are being run on the data

- Captures all commands and logs them

- Manage a list of allowed commands, etc, using Policies

- Block and log all commands that are not allowed. Some commands might be allowed to run

Let’s walk through a simple example of setting this up and using it. For this example I’m assuming you have access to SYSTEM and another schema, for example SCOTT schema with the EMP, DEPT, etc tables.

Step 1 involves enabling SQL Firewall. To do this, we need to connect to the SYS schema and run the function to enable it.

grant sql_firewall_admin to system;Then connect to SYSTEM to enable the firewall.

exec dbms_sql_firewall.enable;For Step 2 we need to turn it on, as in we want to capture some of the commands being performed on the Database. We are using the SCOTT schema, so let’s capture what commands are run in that schema. [remember we are still connected to SYSTEM schema]

begin

dbms_sql_firewall.create_capture (

username=>'SCOTT',

top_level_only=>true);

end;

Now that SQL Firewall is running, Step 3, we can switch to and connect to the SCOTT schema. When logged into SCOTT we can run some SQL commands on our tables.

select * from dept;

select deptno, count(*) from emp group by deptno;

select * from emp where job = 'MANAGER';For Step 4, we can log back into SYSTEM and stop the capture of commands.

exec dbms_sql_firewall.stop_capture('SCOTT');We can then use the dictionary view DBA_SQL_FIREWALL_CAPTURE_LOG to see what commands were captured and logged.

column command_type format a12

column current_user format a15

column client_program format a45

column os_user format a10

column ip_address format a10

column sql_text format a30

select command_type,

current_user,

client_program,

os_user,

ip_address,

sql_text

from dba_sql_firewall_capture_logs

where username = 'SCOTT';The screen isn’t wide enough to display the results, but if you run the above command, you’ll see the three SELECT commands we ran above.

Other SQL Firewall dictionary views include DBA_SQL_FIREWALL_ALLOWED_IP_ADDR, DBA_SQL_FIREWALL_ALLOWED_OS_PROG, DBA_SQL_FIREWALL_ALLOWED_OS_USER and DBA_SQL_FIREWALL_ALLOWED_SQL.

For Step 5, we want to say that those commands are the only commands allowed in the SCOTT schema. We need to create an allowed list. Individual commands can be added, or if we want to add all the commands captured in our log, we can simple run

exec dbms_sql_firewall.generate_allow_list ('SCOTT');

exec dbms_sql_firewall.enable_allow_list (username=>'SCOTT',block=>true);Step 6 involves testing to see if the generated allowed list for SQL Firewall work. For this we need to log back into SCOTT schema, and run some commands. Let’s start with the three previously run commands. These should run without any problems or errors.

select * from dept;

select deptno, count(*) from emp group by deptno;

select * from emp where job = 'MANAGER';Now write a different query and see what is returned.

select count(*) from dept;

Error starting at line : 1 in command -

select count(*) from dept

*

ERROR at line 1:

ORA-47605: SQL Firewall violationOur new SQL command has been blocked. Which is what we wanted.

As an Administrator of the Database (DBA) you can monitor for violations of the Firewall. Log back into SYSTEM and run the following.

set lines 150

column occurred_at format a40

select sql_text,

firewall_action,

ip_address,

cause,

occurred_at

from dba_sql_firewall_violations

where username = 'SCOTT';

SQL_TEXT FIREWAL IP_ADDRESS CAUSE OCCURRED_AT

------------------------------ ------- ---------- ----------------- ----------------------------------------

SELECT COUNT (*) FROM DEPT Blocked 10.0.2.2 SQL violation 18-SEP-25 06.55.25.059913 PM +00:00

If you decide this command is ok to be run in the schema, you can add it to the allowed list.

exec dbms_sql_firewall.append_allow_list('SCOTT', dbms_sql_firewall.violation_log);The example above gives you the steps to get up and running with SQL Firewall. But there is lots more you can do with SQL Firewall, from monitoring of commands etc, to managing violations, to managing the logs, etc. Check out my other post covering some of these topics.

SQL History Monitoring

New in Oracle 23ai is a feature to allow tracking and monitoring the last 50 queries per session. Previously, we had other features and tools for doing this, but with SQL History we have some of this information in one location. SQL History will not replace what you’ve been using previously, but is just another tool to assist you in your monitoring and diagnostics. Each user can access their own current session history, while SQL and DBAs can view the history of all current user sessions.

If you want to use it, a user with ALTER SYTEM privilege must first change the initialisation parameter SQL_HISTORY_ENABLED instance wide to TRUE in the required PDB. The default is FALSE.

To see if it is enabled.

SELECT name,

value,

default_value,

isdefault

FROM v$parameter

WHERE name like 'sql_hist%';

NAME VALUE DEFAULT_VALUE ISDEFAULT

-------------------- ---------- ------------------------- ----------

sql_history_enabled FALSE FALSE TRUEIn the above example, the parameter is not enabled.

To enable the parameter, you need to do so using a user with SYSTEM level privileges. Use the ALTER SYSTEM privilege to enable it. For example,

alter system set sql_history_enabled=true scope=both;When you connect back to your working/developer schema you should be able to see the parameter has been enabled.

connect student/Password!@DB23

show parameter sql_history_enabled

NAME TYPE VALUE

------------------------------- ----------- ------------------------------

sql_history_enabled boolean TRUEA simple test to see it is working is to query the DUAL table

SELECT sysdate;

SYSDATE

---------

11-JUL-25

1 row selected.

SQL> select XYZ from dual;

select XYZ from dual

*

ERROR at line 1:

ORA-00904: "XYZ": invalid identifier

Help: https://docs.oracle.com/error-help/db/ora-00904/When we query the V$SQL_HISTORY view we get.

SELECT sql_text,

error_number

FROM v$sql_history;

SQL_TEXT ERROR_NUMBER

------------------------------------------------------- ------------

SELECT DECODE(USER, 'XS$NULL', XS_SYS_CONTEXT('XS$SESS 0

SELECT sysdate 0

SELECT xxx FROM dual 904[I’ve truncated the SQL_TEXT above to fit on one line. By default, only the first 100 characters of the query are visible in this view]

This V$SQL_HISTORY view becomes a little bit more interesting when you look at some of the other columns that are available. in addition to the basic information for each statement like CON_ID, SID, SESSION_SERIAL#, SQL_ID and PLAN_HASH_VALUE, there are also lots of execution statistics like ELAPSED_TIME, CPU_TIME, BUFFER_GETS or PHYSICAL_READ_REQUESTS, etc. which will be of most interest.

The full list of columns is.

DESC v$sql_history

Name Null? Type

------------------------------------------ -------- -----------------------

KEY NUMBER

SQL_ID VARCHAR2(13)

ELAPSED_TIME NUMBER

CPU_TIME NUMBER

BUFFER_GETS NUMBER

IO_INTERCONNECT_BYTES NUMBER

PHYSICAL_READ_REQUESTS NUMBER

PHYSICAL_READ_BYTES NUMBER

PHYSICAL_WRITE_REQUESTS NUMBER

PHYSICAL_WRITE_BYTES NUMBER

PLSQL_EXEC_TIME NUMBER

JAVA_EXEC_TIME NUMBER

CLUSTER_WAIT_TIME NUMBER

CONCURRENCY_WAIT_TIME NUMBER

APPLICATION_WAIT_TIME NUMBER

USER_IO_WAIT_TIME NUMBER

IO_CELL_UNCOMPRESSED_BYTES NUMBER

IO_CELL_OFFLOAD_ELIGIBLE_BYTES NUMBER

SQL_TEXT VARCHAR2(100)

PLAN_HASH_VALUE NUMBER

SQL_EXEC_ID NUMBER

SQL_EXEC_START DATE

LAST_ACTIVE_TIME DATE

SESSION_USER# NUMBER

CURRENT_USER# NUMBER

CHILD_NUMBER NUMBER

SID NUMBER

SESSION_SERIAL# NUMBER

MODULE_HASH NUMBER

ACTION_HASH NUMBER

SERVICE_HASH NUMBER

IS_FULL_SQLTEXT VARCHAR2(1)

ERROR_SIGNALLED VARCHAR2(1)

ERROR_NUMBER NUMBER

ERROR_FACILITY VARCHAR2(4)

STATEMENT_TYPE VARCHAR2(5)

IS_PARALLEL VARCHAR2(1)

CON_ID NUMBER

You must be logged in to post a comment.